They’re boats. Not much happens without their keels. You’d think that the average boat person would be all over what’s up with the big heavy things down-under their boats. But most don’t and for good reason. The engineering involved intimidates: The Beach Boys would never, ever write a song “Hull John B.” And Jimmy Buffett, as much as he loves to fly, never got far with a tune called “Changes in Laminar Flow, Changes in Lateral Resistance.”

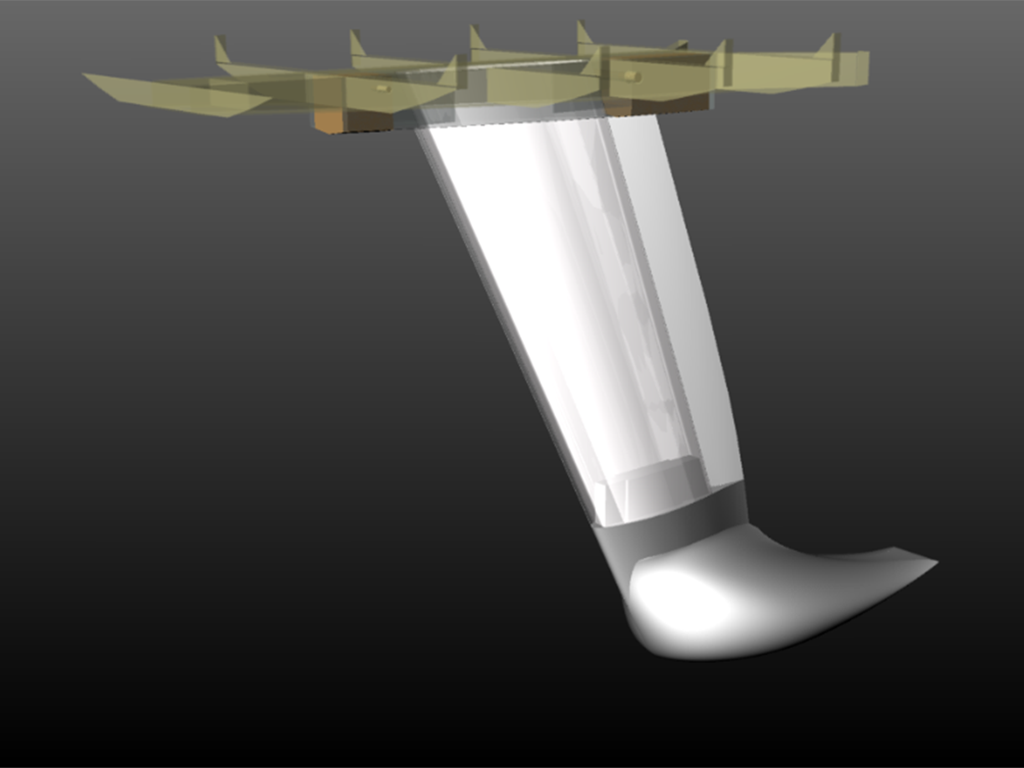

But irrational keel fear is pretty darn dumb, once you know what it does and why. So let’s start with how a keel is attached to your boat. And for that, let’s have a marine-engineering moment and take a deep dive into the bulb keel on our 50-foot daysailer Ginger, which we finished back in 2007 at Brooklin Boat Yard, in Brooklin Maine.

What keeps this lovely keel under Ginger, and not lying on the bottom somewhere, is an interesting nautical puzzler, indeed.

Crazy Glue Doesn’t Work

For starters, no matter how much adhesive, basic wood framing, or any sort of rudimentary attachment systems you might have, nothing easy and simple keeps a keel, a keel. These big heavy underwater wings are too massively loaded, and work too hard to be attached by anything basic. What’s required is a bomb-proof connection technology that conjoins the massive bulb at the bottom of a modern keel to the relatively light engineering and framing at the bottom of a modern hull.

There are several paths to brokering that structural handshake: We’ve spec’d vertical bolts in some boats that straight run up from the vertical axis of keel, through holes in the hull. And are attached with big honkin’ nuts. Like 6-inch, giant suckers that need special wrenches to tighten. But nuts and bolts kind of drive us kind of nuts. They loosen. They eat up interior volume. They need special tools. Heaven forbid you cross thread one. Oh boy.

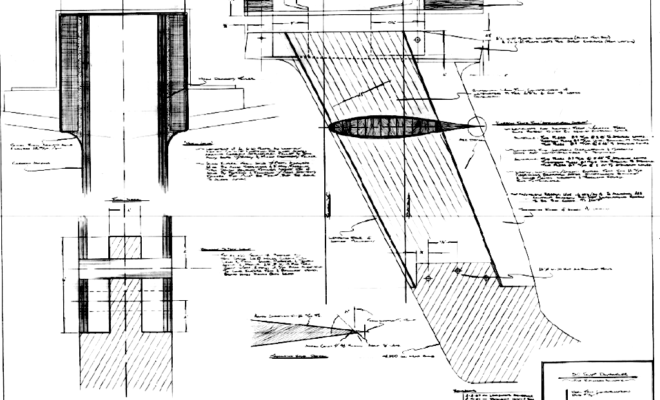

Note the green, bronze frame that fits flush into the hull. It strong yet is designed with elements that can shear away in an emergency.

Instead, for Ginger we developed a keel with its own attachment structure, that could be fitted into a watertight socket in the bottom of the hull. It’s not exactly how airplane wings attach into a plane fuselage. But it’s close. And we love how tough the green structural attachment frame in the sketch to the right turned out to be: That’s the bronze ‘gridwork’ fabrication — a structural element that creates a water-tight framework in the hull’s structure. This beefy sucker, that can never, ever move, is then pinned in place by a giant, horizontal rod that slides along the axis of the keel. Connecting keel to boat. Nice and tough.

We like a massive structural shear pin. They don’t come loose, they address the load and lack the typical corrosion problems that happen in the creases in keel-to-hull joints that conventional bolts will create. The pins are repairable. And they also can be engineered to allow forgiveness in case of collision. In the worst case, a secondary smaller shear pin fails when the grounding loads force the keel to rotate about its mount resulting in saving the hull, the boat, and you.

Read the rest of this article on stephenswaring.com to learn how lobster pots and load distribution affect keel design.