The steamboat was the first form of engine powered travel across water and from about 1820 to 1940, Connecticut’s coastal and riverside residents relied on them as much as we do today on cars and busses for quick transportation. Travel on the Connecticut River was very downstream until the steam power allowed boats to move against the current. On the coast, Long Island Sound was ideal for cultivating use of the steamboat as an innovative mode of transportation to bypass poor roads and an absence of bridges.

As a Connecticut resident in the 19th century, it would take far longer to travel on land than the eight miles an hour it took in a comfortable steamboat. The speediest route by stagecoach for New York went north from New Haven to Hartford and on to Boston, but that trip took 48 hours and stagecoaches and other land conveyances had limited space for freight. A sailing merchant marine serviced New York and Boston, but passage between the two cities were subject to unpredictable sea and climate conditions, taking three to five days after navigating out of a crowded harbor.

Steam power over sail won and demand for these vessels expanded rapidly, especially in Long Island Sound and its northern shore dominated by the Connecticut coastline and its heavily populated ports. Well into the first quarter of the 19th century, several boat lines quickly formed servicing Bridgeport, Norwalk, New Haven, Hartford, Norwich and Stamford to New York. In the 1800s New York City grew into the nation’s distribution center for western wheat and provisions for eastern cities; just beyond the other end lay Boston and its hub of nearby of manufacturing centers. Textiles and shoes from Massachusetts’s flourishing factories were shipped to New York for points west or abroad.

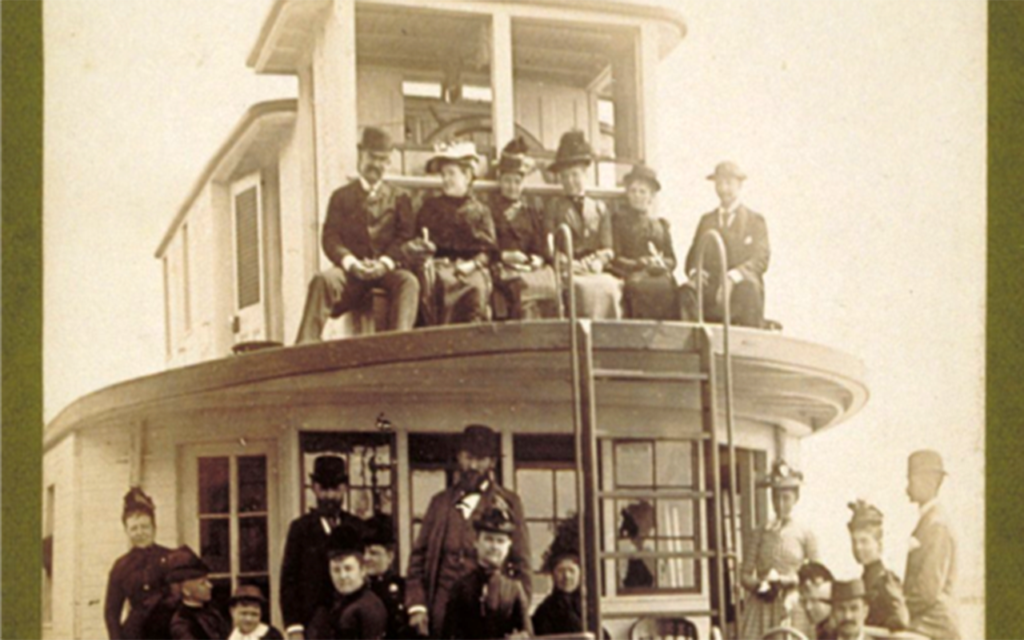

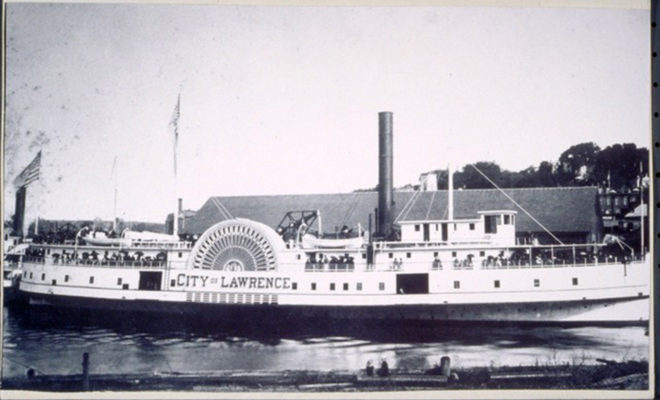

Up to and during the Civil War, steamboats were mostly utilitarian and an affordable method of moving freight. After the war ended, “Victorian Ladies” emerged as the fashionable floating palaces with crystal chandeliers, rosewood settees, and fine dining accommodations. An expanding middle class traveled by steamer to New York and Boston, but also to a bevy of new hotels, picnic groves, and seaside resorts. The City of Lawrence became part of the Norwich line in 1867, and was first iron-hulled steamer on Long Island Sound. Well appointed, the steamer had 78 staterooms and 250 barracks-style berths with a main deck completely enclosed for freight cargo while the upper dining salon provided scenic coastal and river views.

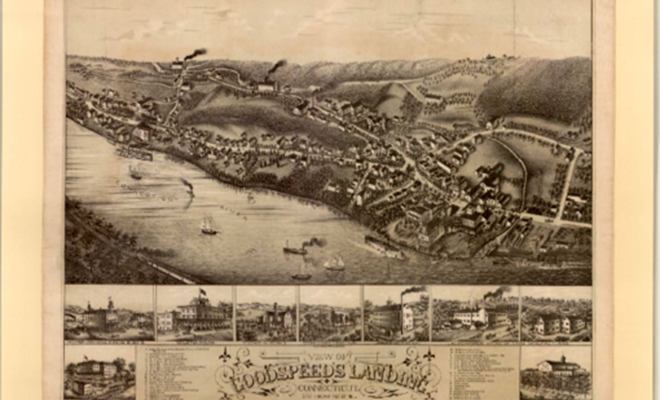

William H. Goodspeed, general manager of the Hartford and New York Transportation Company, operated a line of steamboats on the Connecticut River. His steam ferry the Goodspeed brought Connecticut Valley Railroad passengers across the river to East Haddam to visit his opera house, which opened in 1876.

With boilers filled with scalding water under pressure, steamboats were inherently dangerous. After several horrific accidents occurred, Congress passed the Steamboat Act of 1852 requiring construction standards, inspections, and measures to prevent fire and collisions. One nightmarish disaster happened in 1833 to The New England en route from New York to Hartford while traveling with The Boston carrying 70 passengers and 20 crew. Engaged in a friendly race, a common occurrence between commercial vessels, the two parted at the mouth of the Connecticut River. Shortly after The New England developed engine problems, stopped for repairs, and carried on upriver to Essex to lower a small boat and gather a passenger. Unbeknownst to crew and passengers, excess steam had built up from the racing that had not been properly released, suddenly both boilers exploded creating a “sound like the crack of a cannon”. Thirteen people died and even more were scalded as a result.

In the mid-1850’s railroad companies began to acquire steamboat lines, working in tandem until the Depression bankruptcy doomed this mode of transportation forever. Also a contributing factor was that steamboats were slow, noisy, unreliable, often times unsafe and consumed enormous quantities of wood for fuel. These stately boats ruled trade and travel in the 1800s and early 1900s, but were unable to withstand competition from railroads and automobiles. A romantic era of “Victorian Ladies” had its last voyage and their hay day ended, leaving a legacy of nostalgia and wistful yearnings for the past.

Image Source: www.ctdigitalarchive.org