By Richard King.

Holly Martin, a 29-year-old sailor from Round Pond, Maine, dropped anchor beside the island of Nuka Hiva. She had completed a 41-day open water singlehanded passage from Panama to the Marquesas aboard her 27-foot sloop Gecko. Now she looked around at a bay edged by steep green mountain peaks. Even before she began this passage, likely the longest of her intended circumnavigation, she acknowledged, “This is definitely the biggest thing I’ve ever done in my life.”

Although correspondence is a challenge from the South Pacific, Martin is still very much a 21st-century sailor. She posts on Instagram. She raises money via Patreon. And she has a YouTube channel called “Wind Hippie Sailing” that regularly has more than 30,000 views per episode. The video tour of her boat and systems has over 125,000 views so far. Her videos use footage that she takes with her GoPro camera of herself, mostly talking unscripted, even as something goes wrong and she works through a problem. For example, when some floating underwater debris thwacked her hull while she was under way toward Isla Pedro Gonzalez, just before the long passage to the Marquesas, Martin filmed herself explaining in calm tones what had just happened. She explained how she’d been checking for water under the floorboards, and that when she arrived at anchor in a few hours she would dive on the hull to do a full inspection. “Not such a great thing to do right before you leave for a giant solo Pacific crossing,” she said to the camera. Then, spliced into the video seconds later, came the update: “Just dove on the hull, everything looks cool.” Whatever it was had banged a chunk of paint off Gecko’s iron keel, but otherwise all was sound.

Martin has documented her voyage on her YouTube channel “Wind Hippie Sailing” filming herself as she makes repairs and makes a life onboard Gecko.

Martin has documented her voyage on her YouTube channel “Wind Hippie Sailing” filming herself as she makes repairs and makes a life onboard Gecko.

“Wind Hippie Sailing” on YouTube is one third travel reality show, one third subtle self-empowerment, and one third how-to on cruising, the latter being useful discussions on small boat maintenance, underway strategies, and logistics in foreign ports. From her backyard in Maine, Martin takes the viewer through the fitting out of her Danish-built Grinde double-ender, and then films snippets of her first wintery leg of the journey from Pemaquid Harbor down to Oriental, North Carolina. With self-deprecating humor, Martin shares the rough weather, the frustrations, and the moments of joy, whether that’s with the satisfaction of a new rigging installation or a vision of an exceptional sunset.

Holly Martin knows what she is doing, and knows when to admit when she does not. Born in New Zealand to American world-cruising parents, she literally grew up on a boat for the first years of her life. Her parents moved to Round Pond about 18 years ago after sailing for more than a decade on a small sailboat with their three kids, including a few years in high Arctic latitudes.

Martin stands at the stern of Gecko on the August 2018 day when she bought the boat in Salem, Massachusetts. Photo by Jaja Martin

Martin stands at the stern of Gecko on the August 2018 day when she bought the boat in Salem, Massachusetts. Photo by Jaja Martin

Martin, perhaps consciously, or, maybe even without thinking about it, barely mentions in her videos and in her writings that she is a female sailor voyaging alone. We’re nearing a time when it won’t even be notable, because Martin sails in the wake of at least 70 years of female singlehanded sailors. Hundreds of women, likely over a thousand by now (it’s nearly impossible to calculate), have crossed oceans alone under sail. These include the youngest singlehanded circumnavigating sailors of any gender, Laura Dekker and Jessica Watson; the oldest of nonstop solo circumnavigators, Jeanne Socrates (at 76); and some of the fastest nonstop solo circumnavigating racers are also women, such as Ellen MacArthur and Denise Caffari. Of the 33 entrants in the current Vendée Globe singlehanded round-the-world race, six are women.

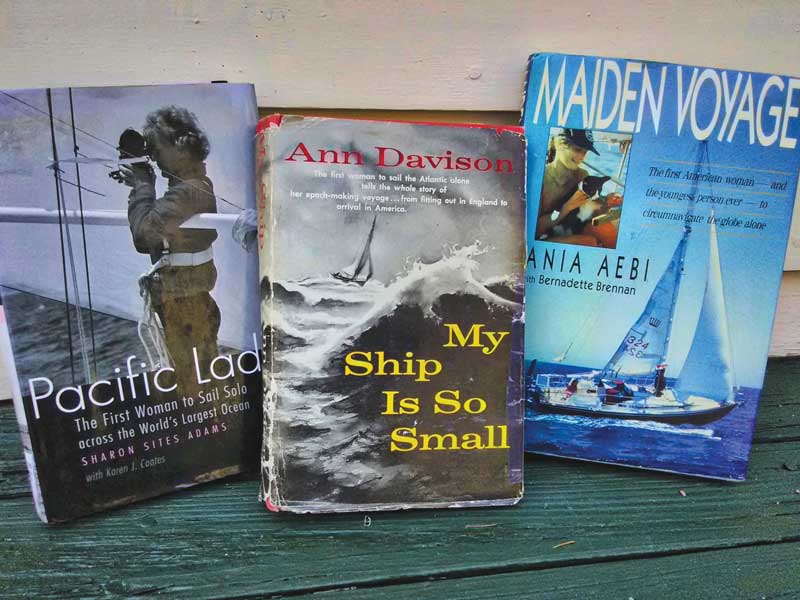

Perhaps the most famous female pioneer in singlehanded sailing was Tania Aebi, who sailed a new 26′ Contessa around the world alone in the late 1980s. Her boat had been purchased by her hard-driving and deep-pocketed father, who wanted her to circumnavigate because he believed that his daughter needed some direction and to learn more about responsibility. Aebi was not only the first American woman to circumnavigate alone, but she was also the youngest person from anywhere at the time. In the years just before GPS, Aebi taught herself celestial navigation, penciled on plotting sheets and paper charts, and she used headphones and a radio direction finder pointed toward lighthouses to estimate her location.

Yet a decade before Aebi, three women, independent of each other, completed a solo circumnavigation

in the same year. In March of 1978 Krystena Chojnowska-Liskiewicz, from Poland, became the first woman ever in her 31′ Mazurek. Naomi James and Brigitte Oudry, from New Zealand and France respectively, each completed their circumnavigations months later by going in opposite directions around Cape Horn.

A decade before them, in 1965, Sharon Sites Adams, who was the manager of a dentist’s office and recently widowed, first learned to sail when she was 34. Within months she sailed alone from California to Hawaii. Four years later, on a sponsored new 31′ Mariner ketch, Sea Sharp II, she sailed singlehanded from Japan to San Diego. In her co-authored account, Pacific Lady, she is forthright about times of loneliness and fear and being underestimated. “Critics have accused me of being too independent, and I’m sure that’s true,” Sites Adams wrote. “Reporters lambasted me when I sailed to Hawaii. One asked, ‘Why?’ when it would have been cheaper to fly. They called me a foolish housewife. They psychoanalyzed me. Some asked who gave me the right to sail the ocean alone.”

A decade before Sites Adams, and 68 years before Holly Martin departed from the coast of Maine, Ann Davison was the first woman, as far as we know, to sail singlehanded across an ocean. Davison traveled across the Atlantic aboard Felicity Ann, a 23-foot wooden sloop in 1952. Davison, like the other early adventurers, did not have access to long-range weather reports at sea. She had no radar, no GPS, no two-way radio, no EPIRB, and, most significantly to those singlehanders after her—just ask Holly Martin—Ann Davison did not have either mechanical or electronic self-steering. She simply, wearily, sat at the tiller day after day. Sometimes she was able to tie the tiller for a few moments or adjust the sails and clip the tiller to guy lines so Felicity Ann could steer itself. More often, though, she hove-to or just took the sails down to catch up on sleep below, having to content herself with making no miles at all. Nor was Davison lucky. She sailed her trans-Atlantic during the rare year in which the normally consistent trade winds were elusive, so she had to painfully beat and claw and drift her boat across to the Caribbean. It took her 65 days to sail from the Canaries to Dominica.

Ann Davison had been a pilot of small planes before being a sailor, and she was a gifted writer, too. The story of her crossing, My Ship is So Small, is a work of literature, although unfortunately out of print. Chronologically and stylistically closer to Joseph Conrad, but with a sense of humor, Davison set a new standard for poetic insight in a sea story.

Beyond her imagination in the 1950s were the type of technologies in Holly Martin’s world today, both for storytelling and for sailing. Yet their experiences at sea are far more alike than different. Davison wrote a passage that I suspect Martin might especially appreciate after arriving at Nuka Hiva: “I know by now that the glitter of romance as seen from afar often turns out to be pretty shoddy at close quarters, and what appears to be a romantic life is invariably an uncomfortable one, but I know, too, that the values in such living are usually sound. They have to be, or you don’t survive. And occasionally you are rewarded by an insight into living so splendid, so wholly magnificent, you can be satisfied with nothing less ever after, so that you go on hoping and searching for another glimpse for the rest of your life.”

In Round Pond, Maine, Holly’s mother, Jaja, who now, among other things, runs the sailing club at her local YMCA, spends part of her week with her husband, Dave, helping Holly with logistics and weather information over Gecko’s inReach Satellite Communication system. The afternoon that I spoke to Jaja, she had just received a text from Holly, requesting some help on the tides in French Polynesia.

“Ever since she was little kid, she has always wanted to do this,” Jaja explained. “It was inevitable.”

After her childhood cruising at sea, Holly studied marine biology in college, then taught with sailing programs, such as Maine’s Ocean Classroom, and spent four seasons in Antarctica working as a research support tech, which included running small boat operations around the ice. She used these positions to earn money and to build her knowledge for her present voyage. Because of all those previous female mariners and likely more because of her comfort in her own skin, she is not out at sea aboard her Gecko to prove anything to anybody.

“Holly doesn’t look at this like a trip,” her mother said. “She looks at it as a way of life. So, for her, it’s not something that she is going to start or finish. She’s not going to say I’m going back to the States. She might say, I’m going to the States. She just wants to circumnavigate. And she’s happy to do it alone. But she might bring someone else aboard if she wants, or stop somewhere for a while. She is unapologetically herself.”

✮

Richard King is the author most recently of Ahab’s Rolling Sea: A Natural History of Moby-Dick.

Follow Holly Martin on Instagram @boatlizard, on YouTube at “Wind Hippie Sailing,” and at Patreon at Patreon.com/WindHippie.

READ MORE at maineboats.com