Predicting Winners and Losers in a Warming Arctic

Posted

Last Updated

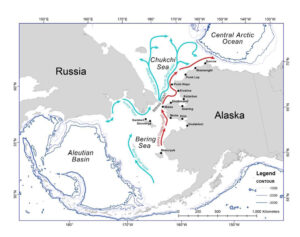

Habitat for key prey species may shrink dramatically if climate change continues on its current trajectory, new research shows.

By the end of this century, Arctic ocean bottom temperatures may be too warm for most seafloor-dwelling invertebrates that currently reside there, a new study finds. Potential “losers” include snails, mussels, and other animals that are important prey for valuable commercial fish species and marine mammals such as Pacific walrus. Arctic coastal communities also depend heavily on the arctic marine ecosystem for subsistence.

NOAA Fisheries is working with our partners to understand how climate change is transforming arctic marine ecosystems. Our goal is to help the fisheries and communities that are part of them to prepare for the future. This new collaborative study is the first to look at climate change impacts on the entire suite of arctic seafloor invertebrates. An international team of scientists combined biological and climatological data to project how the thermal habitat available to these animals could change over time.

“Our models predict major changes in the seafloor invertebrate fauna that could reverberate through the whole arctic food web,” said study leader Libby Logerwell, NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center. “If warming continues, it is potentially going to make it very difficult for a lot of invertebrates to live there—and for the birds, mammals and humans that rely on them.”

Read more at fisheries.noaa.gov