By Kelly Fretwell and Adrienne Mason.

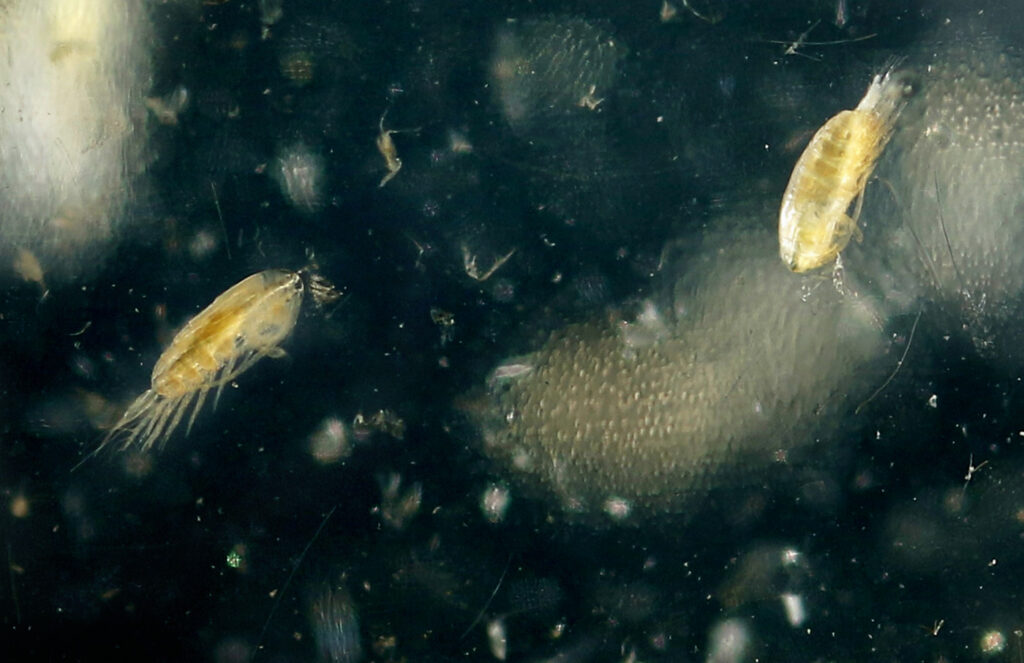

The northeast Pacific Ocean is home to an astonishing array of marine creatures—spiky urchins, multiarmed sea stars, soft sea slugs the color of lemons, and barnacles with their heads glued to rocks. Strolling the seashore or diving below the ocean’s surface, we can see the adult forms of these creatures, but what about their earlier stages? Before they settled down—literally—and moved to the seafloor, almost all started life as zooplankton, marine fauna adrift on the ocean’s currents.

Although zooplankton and phytoplankton, the plantlike drifters that most zooplankton will feast on, are in the water year-round, their populations grow exponentially early in the year. In spring, the days lengthen, the water warms slightly, nutrients flow into the ocean’s surface layers from land or deeper waters, and the phytoplankton bloom. Phytoplankton are microscopic, but as their numbers increase, their chlorophyll and other photosynthetic pigments cause changes in ocean color, which can be measured by satellite imagery and, at high enough concentrations, even become visible to the human eye.

The rapid increase of phytoplankton marks the biological spring in the ocean—zooplankton proliferate with the sudden flush of food. Reproductive strategies among animals that produce planktonic babies vary. Many sessile or slow-moving animals, such as corals and sea urchins, use a sort of mass-mailing technique called broadcast spawning. They release billions of gametes in synchrony, with the strategy that at least some of the eggs and sperm will meet up so fertilization can occur. Barnacles, such as the common intertidal acorn barnacle, are hermaphrodites and use a long flexible penis to fertilize the eggs of their neighbor. A fertilized egg develops inside its parent’s protective, volcanolike shell until it hatches into a larva and is ejected out of the house.

read more at hakaimagazine.com.